In Final Hearing of 2023, FBI Witness Testifies On Secret Recordings Made of 9/11 Defendants

By John Ryan | November 16, 2023 | News & Features, Guantanamo Bay

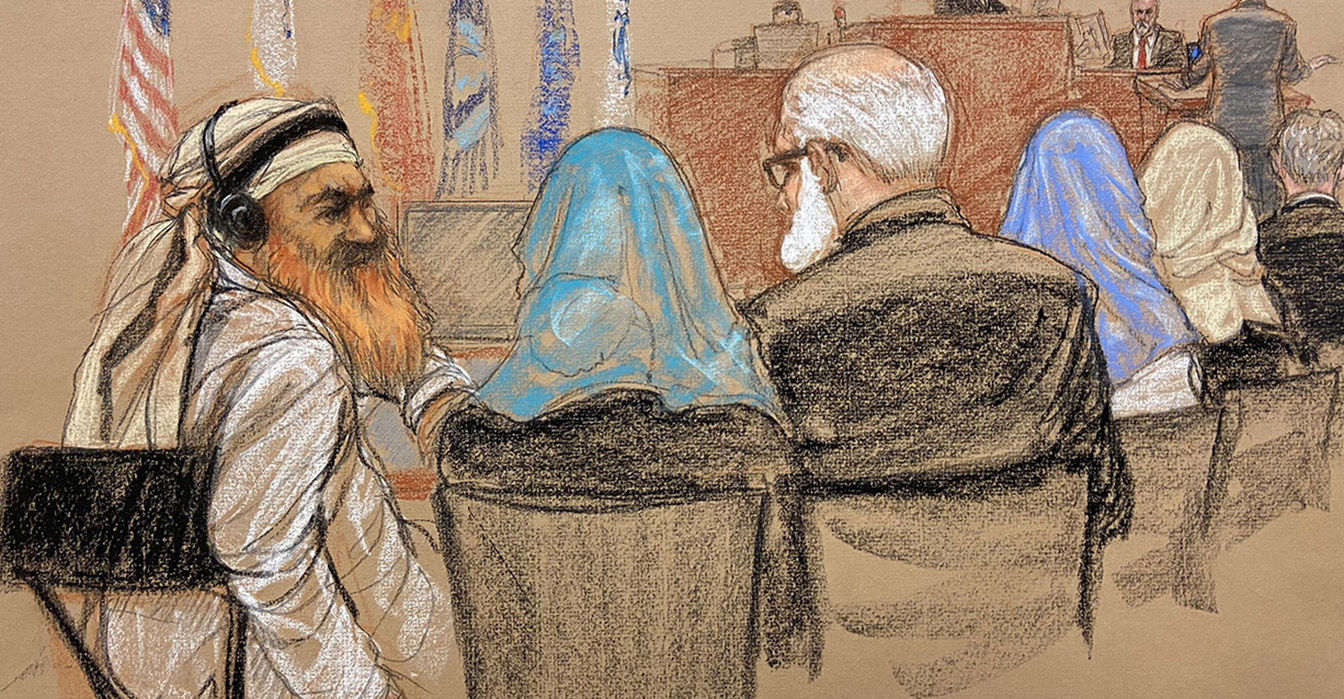

Sketch of Khalid Shaikh Mohammad and members of his defense team by Janet Hamlin.

Guantanamo Naval Base, Cuba – An FBI language analyst testified this week that he made accurate translations of audio recordings that secretly captured the Sept. 11 defendants in conversation with other detainees during their early years at the detention facility on Guantanamo Bay.

Robert Antoon, who has worked out of the FBI’s Detroit office since 2004, testified that he translated about 115 of the conversations for the prosecution team beginning in July 2012, about two months after the defendants were arraigned in the case.

Ed Ryan, one of the prosecutors, displayed in court on Tuesday only a few portions of transcripts of the recordings. In one from October 2007, the accused plot mastermind, Khalid Shaikh Mohammad, appeared to recount to a fellow detainee how he informed Osama bin Laden in the months before the attacks that Sept. 11, 2001, was the intended date. In another transcript from later in 2007, defendant Mustafa al Hawsawi purportedly described to a different detainee how he met with bin Laden about three-to-four days after the 9/11 operation.

“’The Sheikh was whole-heartedly welcoming,’” Ryan read from a paragraph attributed to al Hawsawi.

Antoon told Ryan that "Sheikh" in this context referred to bin Laden, as one of his known aliases.

The government used Antoon's testimony to support its claims that the defendants' other series of incriminating statements – those made to FBI interrogators on Guantanamo Bay in early 2007 – were made voluntarily. Defense efforts to suppress the FBI statements have consumed the bulk of the pretrial litigation since suppression hearings began in September 2019.

Prosecutors first made use of detainee conversations from the detention facility during witness testimony in that hearing, when an FBI agent read extensively from conversations that defendant Ammar al Baluchi had with another detainee.

In October, the judge, Air Force Col. Matthew McCall, ordered the prosecution and the defense teams to file updated pleadings supporting their suppression arguments, with due dates between November and December. At this hearing, which began Nov. 8, McCall granted the prosecution’s request for an extension of time to make their filings.

The judge also announced he was delaying his retirement, initially planned for next April. McCall said he would at least preside over the scheduled four-week hearing in February and a five-week hearing that starts in April and stretches into May. McCall also reiterated that he did not know if the suppression issue would be “ripe” for a decision before he retires.

The government would likely appeal any ruling suppressing the FBI statements, as it did with a suppression ruling in separate military commission earlier this year. The recordings translated by Antoon might become more important evidence for the prosecution if the FBI confessions are ultimately unavailable for use at trial. However, the recordings will also face challenges to their admissibility by defense teams.

James Connell, the lead lawyer for al Baluchi, said outside court this week that his team will contend that the recordings resulted from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment barred by law. He said the government kept the defendants almost entirely in solitary confinement, giving each a limited amount of shared recreation time with one other detainee.

"They created and exploited that outlet to obtain the recordings," Connell said.

On numerous occasions, McCall has suggested that any ruling on the FBI statements will take into account restrictions placed on defense teams in investigating and presenting their cases. Throughout the litigation, the government has blocked the teams from independently contacting CIA witnesses and has asserted a “national security privilege” over other tranches of information. Prosecutors have continued a pattern of intermittently asking the court security officer to interrupt the public feed of the proceedings to the viewing gallery due to potential spills of protected information. At other times, prosecutors have objected to prevent a question from being asked or answered before the security protocol kicked in.

On direct examination by Ryan on Tuesday, Antoon testified that he was able to confirm the identity of the detainees in the detention audio recordings by, in part, comparing them to phone calls allegedly involving Mohammad and two of the other accused co-conspirators intercepted between April and October of 2001.

During her cross-examination on Wednesday, Defne Ozgediz, a civilian lawyer for al Baluchi, attempted to confirm with Antoon that classification guidelines would prevent him from identifying which agency “obtained” the phone recordings in 2001. Ryan objected, explaining to McCall that the prosecution was asserting the national security privilege over Ozgediz asking a “yes or no” question that would not reveal the agency involved.

After a break in which the prosecution and defense teams huddled to discuss the disputed line of examination – a common occurrence in these suppression hearings – Connell claimed that the government was broadening its interpretation of the protective order related to the recorded phone calls. He told McCall that the defense teams were now prohibited from even “determining the contours” of information that the government was making off-limits from the case.

“This is one level even worse,” Connell argued.

“I understand the frustration of some of the parties,” McCall responded, saying defense teams could “add it to the list” of restrictions that they have been documenting throughout the suppression litigation. Ozgediz resumed her questioning of Antoon after telling McCall that she would have to edit her planned examination.

Walter Ruiz, the lead lawyer for al Hawsawi, established in his cross-examination that Antoon did not keep notes about his process of identifying individuals from the recordings and that he did not employ any particular methodology for doing so. Antoon said he was not familiar with certain technologies, such as spectrographic voice identification, that can be used in audio analyses.

“You hear that voice enough times, you know the voice,” Antoon explained.

At several points in his testimony, Antoon said that he based his conclusion about the identities from repeatedly listening to the detention recordings, the 2001 intercepted phone calls and unspecified recordings from court proceedings. He also said that his attendance at the May 2012 arraignment, which lasted about 13 hours, assisted in his identification of the voices.

After Antoon left court Wednesday, however, Ruiz asked McCall to take judicial notice of the fact that al Hawsawi refused to answer questions put to him during the arraignment by the case’s first military judge, Army Col. James Pohl.

“He declined to answer any of them on the record,” Ruiz said, indicating that Antoon likely did not hear his client’s voice at the arraignment.

On Thursday, McCall outlined his intended plan for hearings in 2024, saying he wanted to devote the bulk of the four-week session beginning in February for continued witness testimony related to suppression. About a half-dozen witnesses agreed to by both the prosecution and defense teams, most of them from the FBI, have yet to testify. The two CIA contract psychologists who played lead roles in the agency’s interrogation program, Drs. James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, need to complete testimony they began in January 2020.

Prosecutors also plan to call three additional witnesses – an FBI intelligence analyst, a terrorism expert and a forensic psychologist – to support its claims that the early 2007 interrogations on Guantanamo Bay were voluntary and sufficiently attenuated from the CIA’s earlier coercive treatment. Defense lawyers have said they will want to call up to 100 witnesses to support their cases for suppression if McCall does not rule in their favor prior to leaving the bench. Many of those witnesses are covert CIA officers with knowledge of the abuse of the defendants at agency black sites before their arrival on Guantanamo Bay in September 2006.

McCall resumed the suppression hearings this past September after a year-and-a-half gap in which the defense teams and the prosecution explored plea negotiations that did not result in deals. However, the parties have indicated that they could restart negotiations once the new convening authority, the Pentagon official who oversees the commissions system, gets up to speed on the cases.

Defense lawyers have focused much of their suppression cases documenting coordination between the FBI and the CIA when it came to interrogations, both at the black sites and on Guantanamo Bay. They established, for example, that FBI agents sent questions to the CIA by cable for personnel to ask detainees held at black sites between 2002 and 2006. Many of the same FBI agents were later part of a prosecution task force – established in late 2006 – to structure “clean” interrogations of the detainees on Guantanamo Bay that could be used in military commissions.

FBI witnesses acknowledged accessing CIA reporting prior to conducting the "clean" early 2007 interrogations. They also testified they documented their memorandums of those sessions on CIA laptops. In these sessions, the defendants were neither read their Miranda rights nor given access to legal counsel, even if they inquired about representation, several witnesses have said.

Nevertheless, under questioning by prosecutors, the same FBI witnesses have testified that the defendants participated in the early 2007 sessions voluntarily and that they were free to end the interviews at any time.

Former FBI Special Agent Frank Pellegrino testified in a prior hearing that the CIA interrogation program was “a flaming bag of crap that we got stuck with.” During this hearing, Abigail Perkins, another former FBI special agent who worked the 9/11 case, also criticized the CIA’s control over post-9/11 terrorism interrogations.

“I would have preferred something different,” Perkins said on Nov. 8 in response to questions from David Nevin, one of Mohammad’s civilian lawyers. “I would have preferred to have conducted the interviews myself.”

Perkins said that she and other agents presented arguments to their superiors in what was ultimately an unsuccessful bid to have then FBI Director Robert Mueller get his agents access to CIA detainees. She said that the FBI had a long history of success of using rapport-building techniques to obtain confessions.

“We were the experts at interviewing in these sorts of circumstances,” Perkins said.

CIA personnel briefed the FBI agents on the earlier use of so-called “enhanced interrogation techniques,” or EITs, in late 2006 as part of the preparation for the reinterrogations that took place January 2007 on Guantanamo Bay. FBI Supervisory Special Agent James Fitzgerald, who conducted interrogations with Perkins, testified on Nov. 16 that he was “probably a little bit surprised” about what he learned in that briefing.

Air Force Maj. Kathleen Potter, a military defense lawyer for Mohammad, asked Fitzgerald if some of the agents were concerned about “potential violations of the law.”

“Yes,” Fitzgerald said.

Potter asked Fitzgerald if he and other agents were forced to “look the other way” if detainees raised their past torture by the CIA during the FBI-led January 2007 sessions.

“I was very concerned about allegations of mistreatment and allegations of torture,” Fitzgerald responded.

He testified that, under protocols agreed to by the FBI and CIA, he documented detainee allegations of torture in memoranda that were kept separate from memos that summarized the incriminating statements intended for use in the military commissions. Fitzgerald said he assumed that his superiors in the FBI would be made aware of the allegations and take additional action if needed.

Potter, who conducted her examination from the court's remote hearing room in Virginia, asked him if the FBI’s coordination with the CIA on the interrogations made the bureau “complicit” in crimes committed by CIA actors.

“I don’t believe so,” Fitzgerald said.

About the author: John Ryan (john@lawdragon.com) is a co-founder and the Editor-in-Chief of Lawdragon Inc., where he oversees all web and magazine content and provides regular coverage of the military commissions at Guantanamo Bay. When he’s not at GTMO, John is based in Brooklyn. He has covered complex legal issues for 20 years and has won multiple awards for his journalism, including a New York Press Club Award in Journalism for his coverage of the Sept. 11 case. His book on the 9/11 case is scheduled for publication in September 2024.