Tensions Escalate in 9/11 Suppression Hearings Over Security Interruptions

By John Ryan | February 17, 2024 | News & Features, Guantanamo Bay

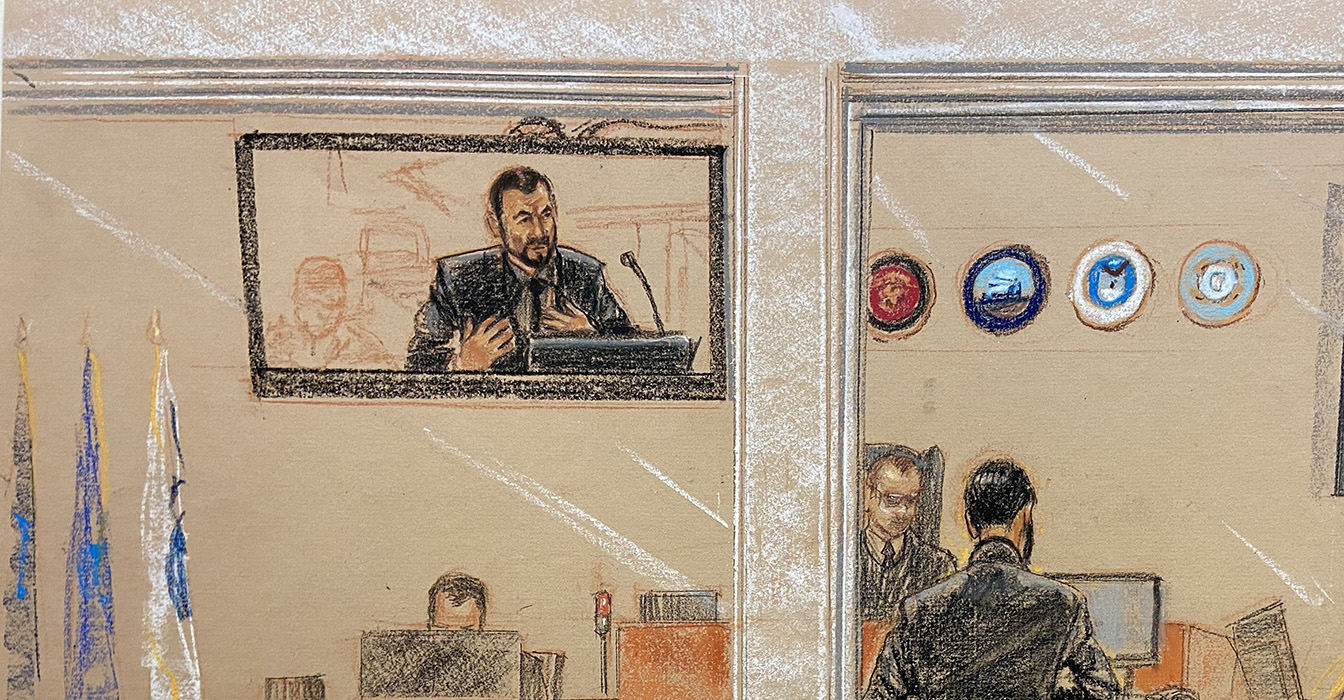

A sketch of defense attorney Walter Ruiz viewed from the courtroom gallery. By Janet Hamlin.

Guantanamo Naval Base, Cuba – Coordination between the CIA and the FBI investigating those responsible for the 9/11 attacks returned to center stage in Guantanamo Bay this week, as court resumed in search of accountability for those who allegedly planned the worst-ever foreign attacks on U.S. soil.

Retired FBI special agent James Fitzsimmons testified that he partnered with CIA personnel in early interrogations of two of the 9/11 defendants while the men were still held by Pakistani authorities after their April 2003 capture. On Wednesday, he said that he and an unnamed CIA officer interrogated Ammar al Baluchi and Walid bin Attash in the days before Pakistani authorities transferred the men to CIA custody, where they endured years of isolation and abuse at secret overseas black sites.

Fitzsimmons also testified that he participated in about 10 days of interviews with a third defendant, Mustafa al Hawsawi, at an undisclosed location after the detainee had already endured the agency’s so-called “enhanced interrogation techniques.” While the timing of these meetings could not be referenced in open court, the testimony appeared to signal that Fitzsimmons spent time at a CIA black site.

Defense lawyers sought Fitzsimmons' testimony to support their argument that coordination between the CIA and the FBI requires the judge to suppress the confessions that FBI agents elicited from the men on Guantanamo Bay in early 2007, after the accused had left the black sites. The CIA’s torture conditioned the defendants to say what their interrogators wanted, defense lawyers claim. The FBI built upon the fruits of the torture, they further assert, in building its criminal case against the four defendants, who also include the accused 9/11 plot mastermind, Khaild Shaikh Mohammad.

James Connell, al Baluchi’s lead lawyer, questioned Fitzsimmons throughout the hearings Wednesday and Thursday. He told reporters outside court that the testimony helped establish the “cradle-to-grave” nature of the FBI-CIA "joint effort," dismantling the myth that the FBI was removed from the rendition program. He also claimed the program was “useless and horribly unnecessary,” pointing to CIA cables documenting early interrogations in Pakistan that showed the detainees were cooperating to various extents prior to entering the black sites. Several of those documents were displayed in court; one CIA cabled noted of al Baluchi: "When asked direct questions, he generally responds with information."

Prosecutors have portrayed the coordination between the FBI and CIA as a natural and necessary response to the attacks that many in the government feared would be followed by even worse strikes. They contend that incriminating statements given to FBI agents on Guantanamo Bay in early 2007 were made voluntarily and were not the products of torture. Prosecutors have said those statements are critical to the case they hope to one day present to a jury of military officers in a trial that could eventually result in the death penalty for the accused.

The judge, Air Force Col. Matthew McCall, is in the midst of a four-week session intended to stretch into March and resume for five weeks in mid-April. He intends to complete testimony from both defense and government witnesses over the contested statements during these sessions. He has told the parties that he may rule on whether to suppress the FBI statements prior to his retirement later this year. If McCall declines to rule, defense lawyers have said they have dozens of additional witnesses to support their cases for suppression.

The recollections offered by Fitzsimmons this week of decades-old experiences were occasionally hazy and made more difficult to parse in a public forum due to the case’s unique national security concerns. Over three direct examinations on Wednesday, exchanges between defense attorneys and Fitzsimmons triggered the courtroom’s security protocol – setting off a flashing red light and interrupting the public feed to the viewing gallery – nine times. As has happened repeatedly in prior sessions, the prosecution asked the court security officer to cut the feed either because of concerns the discussion would stray into classified matters or because the government has asserted a national security privilege over the information. Prosecutors can request the interruption or be directed to do so by a remote entity from the intelligence community, via tablet.

While Judge McCall typically exudes a calm and affable presence in court, he has begun to more frequently express frustration over the interruptions. The first interruption, for example, occurred because of the mention of “unique functional identifiers” or “UFIs” of CIA officers, which are three-digit codes used to protect a person’s covert status. The government's managing trial counsel, Clay Trivett, said after a 50-minute delay that any use of the UFIs for CIA personnel involved in the Pakistan interrogations would have to take place in a closed session.

“Isn’t that why we have UFIs, so that we can use UFIs in open court?” McCall asked, saying it might make sense for him to require lawyers from the intelligence community to come to court.

“I don’t want to yell at you, but sometimes I feel like I should yell at somebody,” McCall told Trivett, saying he knew the prosecutor was a "reasonable" person and not personally responsible for the classifications.

The judge, Trivett responded, could yell at him as much as he would like.

Tensions escalated in the afternoon when the examination by the lead lawyer for al Hawsawi, Walter Ruiz, set off the security light as Ruiz attempted to ask Fitzsimmons about an unclassified document, the nature of which was not revealed to the public. Ruiz told McCall that the government’s limitations were preventing him from being effective in presenting his case and denying his client a public trial.

“We’ve come to accept that as the normal course of things,” Ruiz said. “And it simply cannot be.”

McCall responded that he shared in the defense teams' “frustrations” and said he would consider unspecified “remedies” to sanction the government.

“Perhaps the commission will have to take those remedies,” McCall said, echoing a sentiment he expressed in earlier sessions.

Ruiz continued, saying that he wanted to express clearly for the appellate record that it was becoming impossible to continue to “bend to the will of the government.”

“There may very well come a time when we just stop playing this game,” Ruiz said.

Trivett arose from the prosecution table and said interruptions would continue to happen if the defense teams insisted on going up to the line at which unclassified material crosses over into classified.

“We're also going to make sure that they don’t cross the line,” Trivett argued.

Testimony resumed until, minutes later, the red light was again activated. Ruiz argued to McCall that both the document he was referencing and his questions were well within the guidance provided by the government on what information could be used in court.

“No one says you caught that ball too close to the line,” Ruiz said, likening his team's crafting of a witness examination for a public session to a wide receiver making a catch within the bounds of the football field.

Last fall, McCall indicated that the restrictions imposed on defense teams will factor into any ruling he makes on the admissibility of FBI statements.

The original judge to grapple with the case, Army Col. James Pohl, suppressed the FBI statements in 2018, citing the prohibitions – in place to this day – that prevent the defense teams from independently contacting any CIA witnesses who may have knowledge of the interrogation program. His successor, Marine Col. Keith Parrella, reversed Pohl in 2019 and ordered the defense teams to present a case why the statements should be suppressed. Suppression hearings commenced in September 2019, presided over by the third judge in the case, Air Force Col. Shane Cohen. His retirement in March 2020 and delays forced by the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in McCall overseeing the crucial battle. Since hearings resumed last fall after a lengthy and unsuccessful attempt at plea deals, old wars have been waged anew.

Ruiz reminded McCall that, late last year, his team had filed a motion to resurrect Pohl's initial decision to suppress FBI statements based on the investigative restrictions.

“In the aggregate, this is an unworkable process,” Ruiz said.

As this session commenced, Ruiz asked McCall to dismiss the case against his client for “outrageous government conduct,” claiming the CIA's program met the U.S. Supreme Court standard of behavior that “shocks the conscience.”

Ruiz described the program as an “international criminal enterprise” in which the U.S. government spent vast sums of money to illegally traffic detainees between foreign “torture pits” and brutally extract information for the purposes of both intelligence gathering and building criminal prosecutions. The “violence” and “depravity” of the government’s conduct was unprecedented in American court cases, he argued.

The al Hawsawi team was the first to move forward seeking dismissal of charges against their client based on outrageous government conduct. Ruiz told reporters in advance of the hearing that while the motion significantly overlaps with the case to suppress the FBI statements, it also provides McCall another avenue to sanction the prosecution, either by dismissing the case, removing the death penalty as a sentencing option or suppressing the statements.

In court on Monday, Trivett disagreed. He portrayed the motion as legally unsupported and told McCall that the only remedy open to the defendant was the ongoing effort to suppress the statements. It would have been “outrageous” if the FBI, CIA and other government entities did not coordinate in aggressive efforts to stop the next attacks after 9/11, he countered.

Ruiz's presentation on Monday to establish outrageous conduct was largely opaque to those who viewed from the public gallery. He presented dozens of documents to McCall pertaining to the conditions of al Hawsawi’s confinement that were neither shown on the public monitors nor described in any meaningful detail. Ruiz claimed the restrictions were intended to hide the government's "dirty secrets" rather than protect national security.

Al Hawsawi endured extreme torture at a black site referred to in court as Location 2, or Cobalt, which CIA personnel have previously described as a “dungeon” where merely being present was “an enhanced interrogation technique,” Ruiz explained. He said that, among other acts of violence, interrogators waterboarded his client and also raped him with a rectal exam of such force that it left him with permanent damage.

Prior testimony and declassifications have established that al Hawsawi later spent time on Guantanamo Bay when the CIA used a portion of the detention facility as a secret black site between 2003 and 2004.

Ruiz’s examination of Fitzsimmons on Wednesday failed to establish where or when he interviewed al Hawsawi. In a stilted exchange – interrupted once by the security light – Fitzsimmons referred to an unspecified project and uttered the word “here” when seeking clarification to one of Ruiz’s questions, though it was unclear if he was referring to Guantanamo Bay.

Fitzsimmons testified that he knew at the time he interviewed al Hawsawi that the detainee had been through the agency’s enhanced techniques; the agent did not know which particular methods had been deployed. He testified that al Hawsawi complained of extreme physical discomfort and that staff at the location provided him with medical assistance for severe hemorrhoids.

The government has previously disclosed that some FBI agents were detailed to CIA black sites, and that at least nine FBI agents actually became CIA agents for a period of time during the black site program. In his continued testimony on Thursday, Fitzsimmons testified he was unaware of that arrangement.

Fitzsimmons began his FBI career in 1978, and retired from the FBI in 2005. He wore a headset throughout his testimony in the Guantanamo Bay courtroom to assist his hearing and regularly asked attorneys to repeat their questions.

After court, defense attorneys said they could not make any comment that might reveal the timing or location of the al Hawsawi interviews. The lawyers continued their examinations of Fitzsimmons over several additional hours in a closed session on Friday.

Throughout his public testimony on his time in Pakistan in 2003, Fitzsimmons said that he and his CIA colleague used traditional interviewing techniques during their sessions with al Baluchi and bin Attash. On Thursday, during questioning by Tasnim Motala, one of bin Attash’s civilian lawyers, Fitzsimmons said that the suspects showed no signs of having been mistreated despite Pakistan’s reputation for abusing prisoners. He acknowledged that he told bin Attash that his cooperation would help him avoid the fate of arriving at an American prison where he would be surrounded by violent criminals.

“Doesn’t that sound like a threat?” Motala, who conducted her examination from the court’s remote hearing room in Virginia, asked.

“No,” Fitzsimmons responded. “It’s a statement of reality."

Dr. James Mitchell, one of two CIA contract psychologists who played a lead role in developing the CIA's interrogation program, began his testimony on Monday of the second week of the hearing. He first testified in January 2020.

At the start of court on Wednesday, Trivett revealed that Fitzsimmons was, in fact, one of two FBI agents detailed to the Guantanamo Bay black site to debrief al Hawsawi and other CIA detainees held there. He told McCall that this fact had earlier been declassified by the government but did not make it into the classification guidance for examining the witness in the open session.

“It was unacceptable,” Trivett said of the error, adding that he took full responsibility.

Multiple lawyers from the defense teams rose to tell McCall that the government’s error had prevented the public from learning important facts about the FBI’s role in the black site program.

“The harm has been done,” Ruiz said. “We cannot continue to do business this way.”

About the author: John Ryan (john@lawdragon.com) is a co-founder and the Editor-in-Chief of Lawdragon Inc., where he oversees all web and magazine content and provides regular coverage of the military commissions at Guantanamo Bay. When he’s not at GTMO, John is based in Brooklyn. He has covered complex legal issues for 20 years and has won multiple awards for his journalism, including a New York Press Club Award in Journalism for his coverage of the Sept. 11 case. His book on the 9/11 case is scheduled for publication in September 2024.