The Art of Trial Law, with Stuart Grossman of Grossman Roth Yaffa Cohen

By Emily Jackoway | April 2, 2025 | Lawyer Limelights, Plaintiff Consumer Limelights

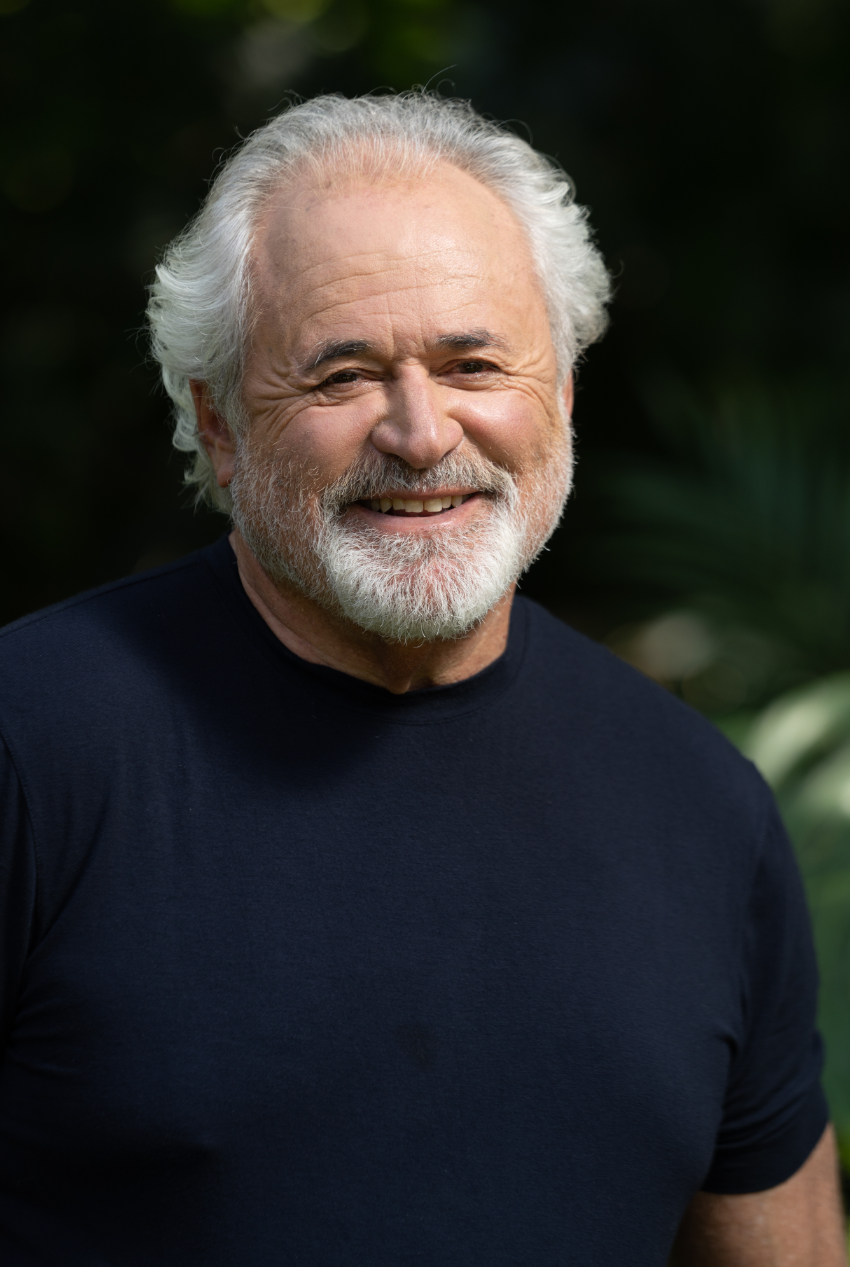

Renowned plaintiffs’ litigator Stuart Grossman is an art lover. In life and in work.

On a recent visit to Paris, Grossman visited La Galerie Dior – the Dior museum. While he was amazed by the pieces, the design of the gallery itself was what moved him most. Sketches would appear in motion on a screen and an electronic process spontaneously brought them to life; technology interwoven with classic art. The technique spoke to Grossman: The museum was taking timeless, trusted design and infusing creativity and innovation. Exactly as Grossman has done throughout his career.

Grossman has devoted more than 50 years to representing victims of catastrophic injury and wrongful death in high-stakes litigation, all while spearheading the firm he co-founded, Grossman Roth Yaffa Cohen. An innovator in the medical malpractice space in the ‘80s, Grossman’s early career was devoted entirely to reimagining the way medical malpractice cases could be tried. As a young lawyer, he brought on the top doctors nationwide as his witnesses – breaking an unspoken code of silence between doctors and giving a new advantage to victims in the courtroom. That outside-the-box way of thinking is a hallmark of Grossman’s work; he views the entire workup of a case, through to the verdict, as a creative process.

He soon moved from bringing his unique perspective to medical malpractice cases to broader negligence cases that needed a new eye to make a difference. If there was an unspoken code of silence among doctors as expert witnesses in Grossman’s early career, in the early ‘90s, there was an ironclad code of silence in the City of Miami Police Department. That is, until Grossman took on a case against the Department on behalf of Antonio Edwards, a young Black man who suffered a heart attack and brain damage after police officers applied a chokehold to him during his arrest. It was the first case that Grossman had taken on as a Section 1983 Civil Rights case, but he was determined to expand into new areas of law so that Edwards could get the medical care he needed. And he did: Edwards’ daily medical care was subsidized with a historic $7.5M settlement plus an additional $1,000 per day for the rest of his life. What’s more, the chokehold was officially banned in Miami.

In 1997, Grossman took on another major Florida entity: corporate electricity giant Florida Power and Light. The company had sent out a contractor to fix a downed power line, cutting power to the surrounding area – including streetlights. With no one appointed to direct traffic, two cars – holding two mothers and their daughters – crashed into each other at an intersection, killing one of the young girls. Grossman took on the case, achieving the largest verdict for the wrongful death of a child at the time in excess of $25M. As in the City of Miami Police Department case, there was concrete change, too: Police are now required to be present at Florida Power and Light construction sites to prevent similar tragedies.

Grossman has also tackled construction litigation on behalf of injured groups. When the Champlain Towers South condominium building in Surfside, Fla., collapsed in 2021, killing 98, Grossman was Wrongful Death Damage Claim Liaison in the ensuing litigation and his firm was co-lead counsel. In the end, the matter settled for $1.1B amongst more than 30 settling defendants.

Lately, Grossman’s artistic canvas has been cases against Florida’s beachside hotels and resorts. In the last 10 years, he’s litigated five cases on behalf of tourists rendered quadriplegic after unknowingly entering dangerous waters behind their hotels. In 2018, Grossman and partner William Mulligan took on a case against the Ritz Carlton South Beach hotel in Miami after a visitor from Long Island, N.Y., crashed into a sandbar at the hotel’s “Ritz Beach” and injured his spinal cord. The potentially dangerous sandbar-like effect of the beach’s topography – known to locals and, the attorneys argued, to hotel management – was not clearly explained to out-of-towners enjoying the hotel’s amenities. The case settled for a substantial amount, allowing the client, Andrew Gallo, care as he begins to attempt to regain the partial use of his limbs. In a case he’s litigating now, Grossman is advocating on behalf of a woman who was also rendered quadriplegic following a lack of warning before crashing into a sandbar. “You can't find a more innocent group than tourists,” says Grossman. “And how can you find a more responsible group than someone who makes huge profits by their operation?”

That passion for standing up for victims, combined with a rigorous preparation and a true flair for the art of storytelling, has delivered justice to his injured clients in the form of hundreds of millions of dollars over the course of his career – all while creating lasting, preventative change. Grossman is a Fellow and former director of the International Academy of Trial Lawyers and a member of multiple Lawdragon guides, including the Lawdragon Hall of Fame. He is one of Florida’s most decorated trial lawyers.

Lawdragon: Can you tell me about this new tourist case?

Stuart Grossman: I want you to imagine two sisters. One is a psychologist who does testing and therapy for children in her town of Fairhope, Alabama. Her sister is an elementary school teacher in her late forties. Both are mothers. From time to time, they would go to the Panhandle, particularly to the Hilton Resort in Sandestin where they would enjoy the beach and shell and do things like that. On this given day, the water condition was under a yellow flag. If you’re not familiar, there's a green flag, where you can go in under any condition. Yellow is like a transition. Red means don't go in the water. And then there's a purple, which would be like a shark attack.

So, the families went down to the beach and into the water. The schoolteacher, whose name is Jane, was in the water when it was getting choppier. She heard a wave building. She tried to get out of the water but was hit in the back of her body and head by a wave as she was trying to exit. However, she was unable to exit because her path was blocked by a concealed sandbar which prevented her from moving forward. Her head was driven into the sandbar and she sustained a hyperflexion injury which rendered her quadriplegic. She was found floating by a young mother with her baby and husband who were sitting on the beach almost at the shoreline. She and others pulled her out of the water. Her face was bruised from where she hit the sandbar and her nose was bleeding. She was unconscious and had foam coming out of her mouth. She recently has returned home after an extended time at the Shepherd Clinic in Atlanta, Georgia.

It just continues to astound me about lack of warnings the hotel provided to guests about the irregular underwater surface and the existence of sandbars such as the one that trapped her. The underwater topography in the Panhandle is irregular with hidden trenches and sudden changes in depth. And there are no warning signs about that, none. So if a tourist needed to get out of the water, his or her pathway could easily be blocked. We went to the resort and conducted our own inspection, and we took one of the leading professors from the University of Miami School of Atmospheric and Water Science. The underwater surface is indeed treacherous. So we're going to proceed with that case. It's my fifth or sixth in a series of quadriplegia cases, dealing with the same element of tourists, hotels, failure to warn and devastating injuries. Nobody wants to learn the lesson.

LD: So many of your cases have had long-lasting, tangible impacts. What are you hoping for with the tourist cases in terms of change for the future of these hotels?

SG: If it were my choice, I’d mandate that at check-in time, a piece of paper be given to the guests that indicate the areas of concern, whether it's the beach, the shallow water, or whatever it might be. But certainly, a warning sign for architectural or geographic or environmental hazards that these hotels have superior knowledge about that the innocent person who's just signing a credit card and going up to the room with maybe no conversation whatsoever with the front desk clerk. We need to take care of our tourists.

LD: Take me back to the start of your career. You started out focusing exclusively on medical malpractice.

SG: Yes. Back then it was very difficult to get doctors to testify against one another. We had what was called the “conspiracy of silence.” I think that in my first job, the biggest contribution I made other than working hard was approaching doctors in a way that attracted them to me and caused them to want to help.

LD: What attracted them to you?

SG: Oh, I don't know. Maybe my earnestness or maybe they knew all along that this was going on. They'd been in enough delivery rooms or operating rooms, and they just thought, you know what? This time I'm going to do it. So, I was up at Harvard with Dr. Emanuel Friedman. He was the chief of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Harvard. I got him to testify when he was America's foremost obstetrician. I hope a lot of kids have benefited by that early work. I think that one of the things that's so significant about our work is that it starts when patients come to lawyers when they don't get answers from their doctors.

Patients come to lawyers when they don't get answers from their doctors.

LD: Thinking about how you thought to bring on huge experts, you've said that creativity is a key to your work. Can you tell me a bit about that?

SG: I think that I look at facts one or two degrees different than other lawyers. There’s a certain artistic element to this, and you have to have good instincts and be sensitive to people because people become the juries and the judges that determine the fate of the client. The creative process only ends with the verdict. I'm talking about the bigger picture. If you and I wanted to paint and we went to the same supply store and you bought canvas and I bought canvas and you bought some oils and I bought the same colors, your painting could be beautiful because of something in you that made it that way.

LD: That’s a great way of thinking of it. On the other side, can you share any challenging moments of cases for you?

SG: Well, from time to time there are judges that are difficult. Fortunately, as time has gone by, I get what I think is some pretty deferential treatment from the bench. But that's earned. I think I know how to act. Every lawyer is going to encounter that difficult judge. You have got to master how to make them feel that they're very much in control, but at the same time win them over.

LD: How do you do that?

SG: Well, I think the most important thing that you can do is say “yes” to the things that don't matter so that when it gets time for something important, the judge does not view you as a complainer. Advocacy mandates that you fight back to an extent, but you’ve got to understand the limits. It's very important to determine what's worth fighting over and what isn't.

The creative process only ends with the verdict.

LD: Do you feel that way about approaching opposing counsel, too?

SG: Absolutely. And in many ways, I don't want them to know what's important to me or perhaps what I'm in fear of them knowing. But you can sure inspire them to dig deeper by being a jerk, not answering interrogatories fully, not returning phone calls. I always try to establish a personal relationship between myself and opposing counsel.

LD: Looking at your historic cases – for instance, the case against Florida Power and Light and the chokehold case – how are those cases indicative of the kind of work that you've been doing ever since?

SG: Lawyers have different motivations. I think the first motivation should always be, “Am I improving the client's life?” I have the capacity to take this disaster and make their life better, recognizing that you can't make it entirely better. You're not empowered to do that. But making it better often involves significant recovery of money because that enables them to get medical care or appliances or physical therapy or mobile devices or home improvements. So, if you keep your eye on, “Can I make it better for the client as opposed to better for myself by earning a fee,” I think you would do well.

Then there are certain cases that have a broader application. The Surfside building collapse case, for instance. I mean, there are hundreds of thousands of condominiums in Florida that are having structural issues for the same reasons – poor maintenance, or perhaps they were built poorly to begin with. The building that collapsed actually had an extra floor tacked onto it that was never permitted or designed. How did they get away with that? Look at the can of worms you expose, from government approvals to construction to architectural malpractice to payoffs. I think that Surfside opened the eyes of homeowners’ associations, condo associations, and others responsible for the wellbeing of their occupants. And then you can come to these cases involving tourists. As I stated, you can't find a more innocent group than tourists. And how can you find a more responsible group than owners and managers of resorts who rent rooms, sell food, drinks, entertainment, etc., but are just going to keep it their dirty little secret that the resort and/or water is unsafe and you can get hurt? So, the answer to your question is you hope to be able to attract cases that have a broader audience and then, through your own individual case, makes society better. I've been blessed to have that opportunity.