Guantanamo’s ‘Hockey Light’ Becomes Focus of Resumed 9/11 Proceedings

By John Ryan | October 7, 2023 | News & Features, Guantanamo Bay

Guantanamo Naval Base, Cuba – Former FBI intelligence analyst Brian Antol did not seem particularly bothered by ongoing interruptions of his testimony on how his agency sought information from 9/11 suspects being held at CIA black sites prior to their arrival on Guantanamo Bay in September 2006.

Discussing his professional background, Antol said that his current consulting company – of which he is the sole member – does “as little work as possible.”

“No worries,” Antol repeatedly told both the judge, Air Force Col. Matthew McCall, and the attorneys examining him when they either apologized for a delay or thanked him for his patience.

“I got nothing but time,” Antol said on Oct. 3, testifying in the third week of the latest pretrial hearing in the Sept. 11 case. His comment may have underscored competing sentiments about the proceedings after a 22-month gap in which plea negotiations began but failed to result in any deals.

Despite his easygoing demeanor, the interruptions revealed the challenges of making steady and sustained progress in the high-stakes suppression hearings that resumed last month, with an untold number of witnesses left to testify about whether the CIA's interrogation program – and the FBI's role in it – requires any confessions by the defendants to be suppressed.

Key to daily progress in the case is how frequently prosecutors rise to alert the court security officer to halt the proceedings over a potential spill of classified or other privileged information. Once instructed, the officer, who sits to the judge's right in the Guantanamo courtroom, triggers the flashing red light positioned between him and the judge – which court observers and participants have long since referred to as the “hockey light.”

Four times on Oct. 2 and 3, the officer hit the light during Antol's public testimony. The device stops the audio and visual feed that is streamed to the courtroom viewing gallery on a 40-second delay to prevent the spill of protected information.

The defense teams’ examination of Antol triggered the interruptions even though the lawyers regularly huddled with prosecutors in advance of asking their questions – a process that itself slows the proceedings. As the light repeatedly went off during Antol’s testimony, McCall called for “open-ended breaks” to allow prosecutors and defense teams to discuss the possible spills and how to best move forward.

McCall regularly encourages lawyers from opposing sides of the courtroom to engage in "cross talk" away from the podium. The judge may have jinxed himself prior to the start of witness testimony for this hearing when he noted that the cross-talk process had prevented any security interruptions in his courtroom since he inherited the case in September 2021.

James Connell, the lead lawyer for defendant Ammar al Baluchi, called Antol to elicit details about how the FBI sought information from detainees held at CIA black sites before their arrival on Guantanamo Bay in September 2006. The defense is seeking evidence of the FBI’s role in coercive CIA interrogations in the effort to suppress confessions their clients later made to the FBI on Guantanamo Bay in early 2007. The prosecution claims that the defendants participated in the FBI interviews voluntarily, and that the FBI’s coordination with the CIA is irrelevant to the admissibility of these statements.

An untold number of witnesses are left to testify about whether the CIA's interrogation program – and the FBI's role in it – requires any confessions by the defendants to be suppressed.

The security officer first triggered the hockey light during Antol's testimony on Oct. 2 as Connell questioned the former analyst about cables sent between the FBI and CIA. Connell was questioning Antol in Virginia, where both were present in the court’s remote hearing room. As a result, Connell had to discuss the suspected spill's national security implications with his team through headsets connecting defense counsel in Guantanamo and Virginia. After about 15 minutes, the parties agreed the exchange did not implicate national security and Connell resumed his examination.

Later that afternoon – just past 4:30 p.m. – the officer again hit the light as Air Force Lt. Col. Nicholas McCue, one of the military defense lawyers for Khalid Shaikh Mohammad, questioned Antol about the preparations he and other FBI personnel made on Guantanamo Bay in early January 2007 before they reinterrogated the detainees. Antol and retired FBI Special Agent Frank Pellegrino, who testified during the second week of the hearing, obtained incriminating statements from Mohammad that the prosecution hopes to use at trial.

The information that set off the second interruption appeared related to – or at least prefaced by – an exchange over whether Antol knew that the CIA exercised some level of “operational control” of the Camp 7 detention facility that housed the former CIA captives on Guantanamo Bay, after their arrival from the black sites. That statement is contained in the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s summary report of the CIA interrogation program released in 2014.

A similar exchange triggered a two-hour delay when Pellegrino testified during the second week. Eventually, Mohammad’s lead lawyer, Gary Sowards, was able to ask Pellegrino if he knew that, while Camp 7 guards wore military uniforms, they were not members of the military. (Pellegrino said he did not know this at the time of interrogating Mohammad in 2007.) With Antol’s testimony, McCall decided to recess for the day rather than wait for a resolution of the operational-control classification issue.

As court started on Tuesday, Oct. 3, Connell told McCall that the government’s shifting classification guidance on what can be asked in court reminded him of a game he played as a kid called “Go to Hell in a Steamboat,” where established players haze a newcomer by constantly changing the rules at every turn. Connell said that there appeared to be a “mismatch” between information that was unclassified for one witness but not another.

Sowards rose to argue that the “ad hoc decision-making” by the government was not to protect national security but to “cover up the CIA torture program.” He said the inconsistencies and inadequate guidance constituted “a chilling effect” that not only complicated court proceedings but also jeopardized the work of defense investigators whose careers depend on maintaining security clearances.

Once McCue resumed his direct examination, Antol testified that he did eventually learn about the Senate report's "operational control" statement. During the January 2007 interrogations, Antol and Pellegrino advised Mohammad that he was in the custody of the U.S. military. Antol testified that he would have given Mohammad the same advisement, even if he had known about CIA operational control. (In a later exchange, Antol explained that he believed the advisement would remain accurate because the U.S. Naval Base on Guantanamo Bay is a military institution.)

Just a half-hour later, the security officer hit the security light for the third time as McCue was examining Antol. McCue had asked Antol about who provided him and Pellegrino with the laptop on which they typed up their notes following each of their four days of interviews with Mohammad. Testimony and documentary evidence in the case has long established that the FBI had to type the memoranda of their interrogations on CIA laptops, though the identities of CIA personnel and other details associated with this process are not public.

Key to daily progress in the case is how frequently prosecutors rise to alert the court security officer to halt the proceedings over a potential spill of classified or other privileged information.

After a break, McCue told McCall that, as this was his first witness examination for the Mohammad team, there was “a certain amount of anxiety” associated with the unpredictable security interruptions.

“Your thought process goes through an extra filter,” McCue said.

Once testimony resumed, McCue confirmed with Antol that he and Pellegrino used a CIA laptop to type up their written notes and that they had to hand the laptop back to “someone else” at the end of each day. The individual daily write-ups were compiled into a single 32-page memorandum on Mohammad's statements.

Prosecutor Ed Ryan conducted his cross-examination of Antol in 30 minutes on Tuesday without any security incidents. Ryan covered ground similar to what he elicited from Pellegrino during the prior week. As did Pellegrino, Antol testified that Mohammad engaged in the sessions voluntarily and was regularly given the opportunity to not participate – an option he eventually chose after the fourth day of interviews.

“We were prepared to go for weeks or months if necessary,” Antol said.

Antol testified that the CIA had no influence on the conduct of the interviews or in the writing of their memoranda. He said that he and Pellegrino relied on the FBI’s investigative efforts after the 9/11 attacks, not what the CIA learned during its black site interrogations.

“We didn’t need any reporting from the CIA,” Antol testified.

The security officer hit the security light for the fourth time that afternoon, as Connell was conducting his redirect examination of Antol and briefly returned to the topic of FBI personnel using CIA laptops on Guantanamo Bay. Initially, there was confusion in Guantanamo and Virginia as to who requested the interruption as it did not appear a prosecution team member had requested it. A few minutes later, the government’s managing trial counsel, Clay Trivett, explained that the court security officer made the decision to stop the feed just as the prosecution was about to give the signal to do so.

From Virginia, Connell remained unclear as to the nature of the national security risk posed by his question. McCall called another open-ended recess to let the parties discuss the matter.

“Does that mean I leave?” Antol, also confused, asked from the remote witness box as McCall left the bench in Guantanamo.

“You can if you want to,” Connell said, leading to audible laughter arriving in the Guantanamo courtroom from the Virginia feed.

Twenty minutes later, Connell was allowed to ask Antol whether the FBI personnel worked in “FBI spaces” on Guantanamo Bay when typing up their interview memoranda on the CIA laptops.

“It was not,” Antol said.

The CIA remains a presence in the courtroom. CIA staff can communicate directly with the prosecution team via a tablet that is located on one of the prosecution tables. Members of Connell’s team first noticed the presence of the tablet in January 2020, during the highly anticipated testimony of Dr. James Mitchell, one of the CIA contract psychologists who helped design the agency’s interrogation program.

Sowards rose to argue that the 'ad hoc decision-making' by the government was not to protect national security but to 'cover up the CIA torture program.'

On at least three occasions during the January session, defense counsel saw a prosecutor react to the tablet by alerting another prosecutor to tell the security officer to cut the public feed. On Feb. 7, shortly before the start of the next session – the last to take place before the pandemic – Connell’s team filed a “Motion to End Apparent Intelligence Agency Disruption of Courtroom Proceedings.”

In oral arguments on Feb. 19, Connell was angered that the judge – then Air Force Col. Shane Cohen – had allowed the CIA to communicate through the tablet after an ex parte presentation by the prosecution team. He argued it appeared as though Cohen had “authorized the installation of a CIA device in the courtroom to allow the CIA externally to assist” the prosecution team.

“Which flies in the face of every idea, not just of due process, but of an adversarial system and democratic values,” Connell argued.

Cohen told Connell that he authorized the tablet because he, like everyone else in the court, had a duty to protect classified information. He said he did not expect the issue to blow up the way that it had.

“And that's on me, because I have never seen this level of distrust and skepticism in any case I've ever tried in 21 years,” Cohen said.

Early in the case, in January 2013, the CIA remotely cut off the public feed without permission from the judge or the security officer. The first judge, Army Col. James Pohl, issued an order preventing any outside agency from interfering with the feed. However, he said it was appropriate for “original classification authorities,” or OCAs, which include but is not limited to the CIA, to observe the proceedings in real time to watch for spills, so long as they themselves could not shut down court or help the prosecution with its case.

Defense lawyers have claimed that unwarranted interruptions of oral arguments or witness testimony – even if they are eventually allowed to ask questions regarding the material – may be crossing the line by interfering with the presentation of their cases.

Antol testified in a closed session on Wednesday, Oct. 4. He briefly testified in open court again on Thursday after the parties had identified additional areas that were not classified. He finished his testimony Thursday evening in a second classified session.

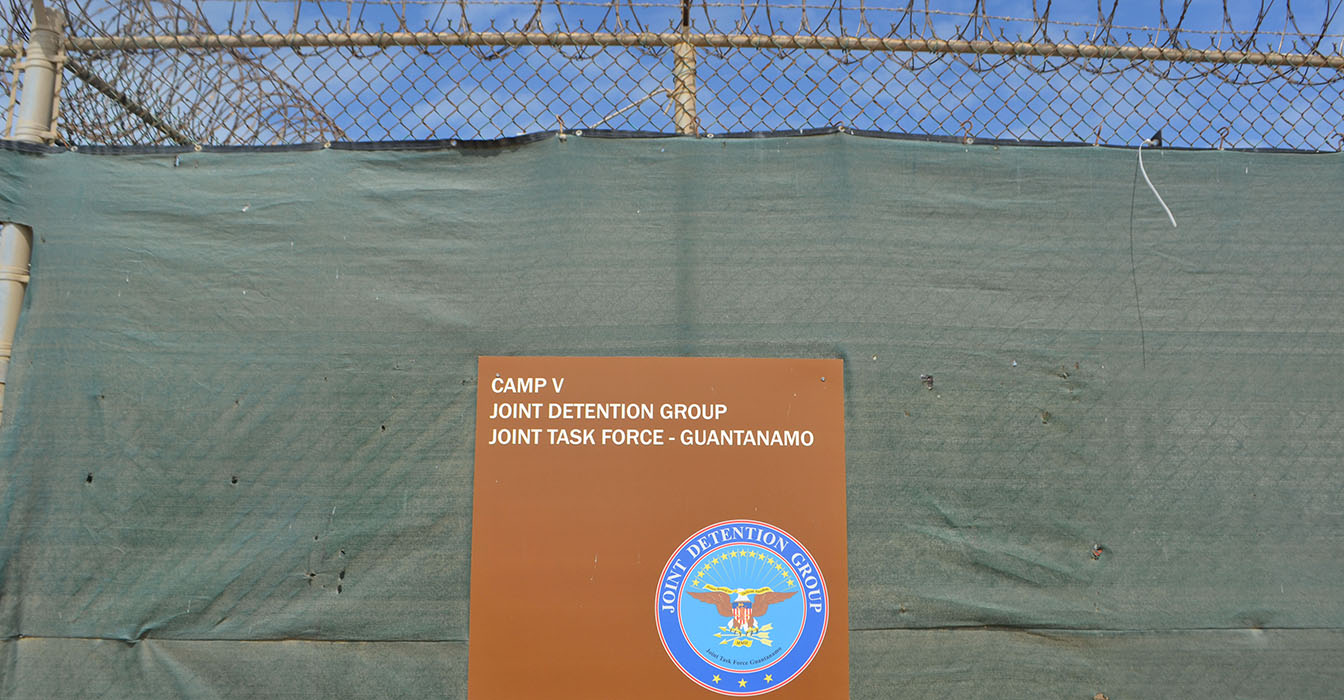

The security light interrupted proceedings twice during the third week in matters unrelated to the suppression hearings. One incident came on Thursday during testimony from the commander of Joint Task Force Guantanamo, Army Col. Matthew Jemmott, related to defense efforts to visit the Camp 5 detention facility under his control. (The task force relocated the 14 former CIA prisoners, including the 9/11 defendants, to Camp 5 in April 2021 due to infrastructure problems with Camp 7.) Another came on Friday as Connell presented oral arguments on a defense motion to compel discovery related to Omar al Bayoumi, a Saudi national who provided assistance to two of the 9/11 hijackers in Southern California.

McCall planned to use the fourth week, beginning Oct. 9, for oral arguments on pending motions and to take classified testimony from Jemmott. He also indicated his intent to use the two-week November hearing to resume testimony for the suppression cases, which could include two FBI witnesses.

However, Antol and Pellegrino – and the FBI witnesses who preceded them – may not be done with their testimony. At the conclusion of Friday's session, Sowards told McCall that the government provided discovery to the defense teams on Thursday evening related to both Pellegrino’s and Antol’s testimony that would require them to testify again. Sowards referred to the discovery as “eye-popping,” though details about its content were not made public.

In a meeting with reporters after court, Alka Pradhan and Rita Radostitz, two of the civilian lawyers on al Baluchi’s defense team, said that the new discovery would also likely necessitate bringing back the FBI witnesses who testified at the start of the suppression hearings in September 2019.

About the author: John Ryan (john@lawdragon.com) is a co-founder and the Editor-in-Chief of Lawdragon Inc., where he oversees all web and magazine content and provides regular coverage of the military commissions at Guantanamo Bay. When he’s not at GTMO, John is based in Brooklyn. He has covered complex legal issues for 20 years and has won multiple awards for his journalism, including a New York Press Club Award in Journalism for his coverage of the Sept. 11 case. His book on the 9/11 case is scheduled for publication in March 2024.